Once Puchiko gets into bed, her venting begins. Usually, that wouldn’t be a problem. However, lately, she has started talking to me openly and boldly. Not many people have an imaginary friend, and talking to one out loud looks strange—to anyone else, it just looks like she’s talking to herself. I really need to admonish her soon. This might be my final mission of the year, but it also intertwines with Puchiko’s Long Winter Break and My Final Mission of the Year.

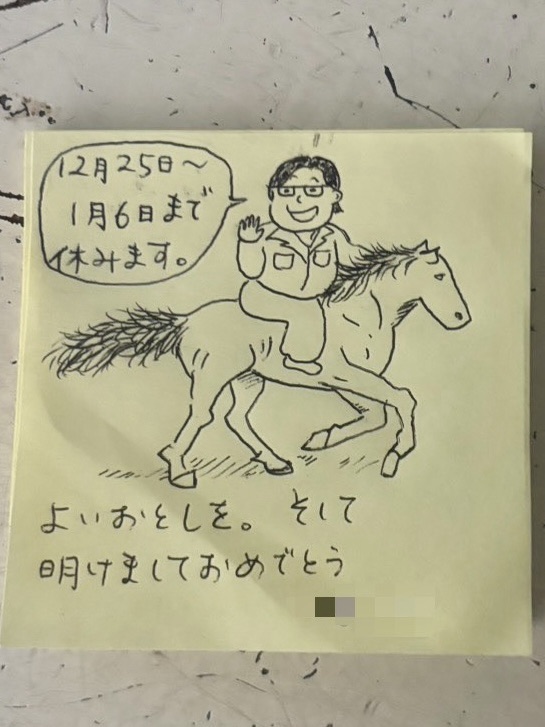

This was Puchiko’s year. She was born in the Year of the Snake, making her the “woman of the year”. But that will end in just a few days as we welcome the Year of the Horse next year.

Puchiko usually works staggered hours, finishing at 4:30 PM, but yesterday she finished at 3:15 PM. Winter break is almost here. Her break is long—from December 25th to January 6th. She originally thought about taking January 7th off as well, but since she needs to save her paid leave for a trip to Belgium in March (to use them up before the Japanese fiscal year ends in March), she decided to work on the 7th. Her current workplace is very flexible and easygoing. Most regular employees stay off from December 25th until January 7th. I think it’s because the organization is run somewhat like a school. This winter break is significant, marking Puchiko’s Long Winter Break and My Final Mission of the Year.

On the way home, Puchiko muttered, “After tomorrow, I’m on break. This is the last time I’ll get to feel this sense of liberation. From next April, winter break will only be from December 29th to January 3rd. I can’t stand it! I mean, in my current job, I have stress, but it’s the kind I can manage. Don’t you think it’s blissful to have this much time off in the middle of that? But where I’m going next, there will probably be people who are impossible to reason with. I’ll be yelled at, face sexual harassment, or deal with ‘customer harassment.’ And yet, I’ll have fewer holidays than I do now! I can’t deal with this! I hate it!”

Anyone reading this is probably thinking, “Stop acting so spoiled.” This sentiment would likely draw a lot of backlash, especially from other Japanese people. I feel like saying the same thing to her, but Puchiko has been soaking in the “hot spring” of this relaxed workplace for over 5 years. The gap between her current environment and a typical workplace is huge, and I realize it’s going to be tough for her—though it hasn’t even started yet.

I don’t mind her venting to me like this. Listening is part of my role as her imaginary friend. However, as I mentioned at the beginning, the more Puchiko establishes my existence, the more naturally she talks to me anywhere. When she first created me, she would only whisper when no one was around. Now, she talks to me while walking through the city or in the hallways at work. To an outsider, she looks like someone who talks to herself a lot. Actually, it might be worse than that. Since she often asks for my agreement, people must wonder, “Who is she talking to?” When she says things like, “Hey! Look at that! What do you think, Jōji?”, it makes me break into a cold sweat. Talking to me seems to drastically reduce her stress, but I wish she would just talk to me in her head instead of out loud. I need to make sure she doesn’t do this at her new job.

Then, there’s what happened on the way home today. Just as Puchiko finished work and started walking, she heard a voice from behind. Her boss, the section manager, came running after her. He handed her a gift of sweets. It was to congratulate her on being hired for her next job, and since it was Christmas Eve, it served as a Christmas present too. “You don’t need to give me anything in return,” he said. (This is where Japanese social cues get difficult. Usually, when Japanese people give gifts or souvenirs, they say things like “No need to return the favor” or “Don’t worry about it.” But you shouldn’t always take those words literally. If you don’t return the favor, they might think, “Oh, they didn’t give me anything back? How rude.” In the case of this manager, I think he truly isn’t expecting anything—though Puchiko will give him something anyway. In Japanese society, it is a basic rule: if you receive something, you give something back.) The manager also told her, “It’s a loss for us, but congratulations.” It really warmed her heart.

Needless to say, I was relieved. Usually, Puchiko starts talking to me the moment she leaves. It was a lucky coincidence that she was walking in silence today, so the manager didn’t catch her talking to thin air. She must have felt relieved too.

On the way to the station, Puchiko was deeply reflecting on the manager’s kindness. For about 20 minutes, she kept muttering, “He’s such a good person. Jōji, the manager is such a good man,” and “I need to become a person like that,” and “He’s such a kind, wonderful boss.” Thanks to that, she spent the whole walk home saying unusually positive and gentle things. Being so close to her, I sincerely wish her mind could always be filled with this much peace and order.

Postscript: